The final truth

It used to be that “going home” – returning to my home town — was a fairly casual affair that didn’t take much planning. Call a relative, say “We’re coming”, and someone would open their doors to us. I went home to see my folks, to see the ocean, to trigger memories: streets and houses, sounds, smells; the wind and the marsh.

These last trips, however, were not about visiting. They were about saying goodbye — winding up a life. And with the end of that life, the thread that connected me directly to my place of birth, to the sweetest childhood memories (in a childhood that was in desperate need of them) was broken.

My father is gone, the last of my direct relatives, and the idea of going home has a new significance. Making the trip must be for a reason other than to visit the folks, because there are no more folks to visit. It must be planned as if I was a tourist. “Home” is not where family is; it is where family was.

In the wake of someone’s death, all the mundane, routine minutiae of a life suddenly loom large. So much to be done all at once: cut off the newspapers, telephone, cable and internet, cell phone; switch the gas and electrical accounts over, stop the insurance policies…oh yeah, I’d better get to the post office before it closes to stop the mail! All that ammo upstairs that Syd didn’t take when he took the firearms must be delivered to the police. But wait — okay, here is a loaded rifle under the couch cushions and a handgun hidden in a book. Um…!!

For all that, it strikes me that dying, well-known in a small town, is not a bad deal for your loved ones. The paperwork was easy (relatively), people were accessible and eager to help. Government issues were handled largely by the funeral home. Only the customer-service representatives of the large nation-wide companies were a bit balky, but they are tied to scripts after all. There might be some merit to all of this activity; one has little time to sit and mourn. At least, during office hours.

I also learned that it is very easy to be misled by prior expectations. My father lived in a house that was not his, but whose exclusive use had been willed to him on the death of his partner (not my mother by the way – my parents were long divorced). Only on his death would the house return to the girlfriend’s estate. He proceeded to live in that house for the next quarter century. The girlfriend had a daughter who was the executor of her mother’s estate. Dad disliked this woman intensely and took every opportunity to explain why. This dislike was echoed by his cousin Joyce and his friends across the street, and so I was steeling myself to face a predatory termagant willing to steamroll over everyone to get her way.

Of course, it wasn’t like that at all. Anna and her sister turned out to be friendly, efficient, understandably anxious to finally get access to the house, but everyone realized the necessity of making the transfer and cleanup as painless as possible. They are, in fact, people I would happily have dinner with. Lesson: Don’t rely on other people’s impressions; they may not end up being yours.

“What will survive of me…?”

An adult human reduced to ashes is surprisingly heavy. My father is in a box, in a plastic bag. It is a strange notion, my father’s earthly remains taking up less space than a stack of CDs. He had preplanned and pre-paid for everything; he wanted no fanfare, and that is what he got. But that might have to change.

My father died. He was my father, but who else was he? That is what I have really been learning about.

My dad joined the army as a teenager, after a few years working in a foundry. He never went to high school. He was in Korea, in Germany; he made a career of it and retired as a Master Warrant Officer after 25 years. He was married at 24, and divorced by 34. There were two kids. In one of those bizarre twists of coincidence, he died 40 years to the day he retired. He was simultaneous solitary, but social; handy and creative – if he couldn’t buy what he needed, he made it. He hunted and fished, built a home on the marsh from scratch, baked and brewed and distilled (some fine stuff, that!), repaired clocks.

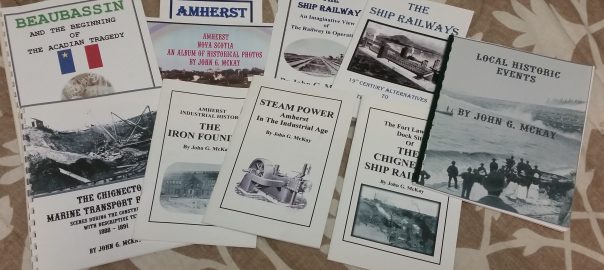

But most of all, he was fascinated by history—mostly military history, and especially local history. He would zero in on details of Amherst or regional history and research the living hell right out of it. He never got past Grade 8 in a formal academic setting, but he may have been the world expert on a tiny specialized sliver of Canadiana – the Chignecto Ship Railway. If there is someone out there who knows more about it, I’d like to meet them.

And he wrote. He wrote fluently and in a mannered style, elaborate and formal. He wrote newspaper columns and letters-to-the-editor; he wrote books and pamphlets he printed and bound himself, and then sold at the local farmer’s market. He wrote of many things, but mostly he wrote of history. His stories were peopled with familiar names. He wrote of things of close familiarity to the denizens of Amherst; they remembered the events or locations, or their relatives had spoken of them. Everyone could relate to something they read, and it seems that his impact, in a cultural, social, and folk-historical context, was far larger than I ever realized. This stubborn, opinionated, white-haired curmugeon was beloved for his ability to bring the past to life and to connect with the lived experiences of the people who bought his books. Almost everyone I spoke to had a story – a book they loved because of some personal connection, or the fact that he made their history – not some abstract set of facts or dates or events in some distant part of the country – but their history, matter.

And when he passed, folks suddenly understood – he took so much of their past with him. There was much handwringing over this. Most people felt that he needed something more than a simple notice on a website. And they are probably right.

However, I am not the person to do this. I never really knew him in the way that is necessary for such a task. My parents split up when I was 10 and my dad pretty much vanished from my life shortly after. I have lived remote from him for most of my life, and when contact was re-established, it was sporadic and managed mostly by email. When I visited it was because I was down home to see grandparents and my mother. At any rate, all I really knew of him was through what he chose to share. I read his books and articles; I knew he was involved in much of the town’s cultural/historical life, but I didn’t have details. I did not understand the impact he had: living 1600 kilometres away, I had no context.

There is a project, though – people who are willing to try and keep his legacy alive through his books by printing and selling them. It will require getting into his computer hard drive (alas I have no password…somehow that detail got overlooked) and finding the files…and this seems to be an immensely important thing to do.

George Bailey had indeed been given a huge gift – the ability to be able to see the impact his life had on others, how things would have been had he not lived. But that’s fiction; only those left behind get that opportunity, along with the regret that the person who has gone will never know how much they were loved. Life may be fragile and transitory, but if there is any way to ensure that the imprint someone leaves on the universe can linger for a while, it surely must be taken.

You may have inherited his gift for writing. I am wiping away a tear as well. Heckuva eulogy! Hugs to you Deb.

This is a beautiful assortment of thoughts that brought more than one of us in my household to tears. How amazing that you’re an advocate for your father’s contribution as a historian and writer. All my love to you, my darling friend. You never cease to amaze me with your written words and your big heart. Thank you for this, it makes me know you a little bit more through your dear dad. <3